Explore the home of the poet, Edna St. Vincent Millay

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Transcript | Email | Bonus Episode

In this episode of the podcast Someone Lived Here, Kendra brings you to Edna St Vincent Millay’s home in Austerlitz, New York. Steepletop, which she named after Steeplebush that grew on the property, was Millay’s home for 25 years. It was also the place she died.

In this episode, we walk through Millay’s home and property to better understand her poetry and her life. After Millay’s death, her sister Norma would become its steward. The episode focuses on Edna St Vincent Millay’s relationship with her mother and her sister.

Thank you to Holly Peppe, Mark O’Berski, and the entire Edna St Vincent Millay Society. The home is not currently open to the public, due to a financial crisis. You can learn more about the property and how to donate, here.

Music by Tim Cahill. Icon artwork by Ben Kirk. Transcription by Sam Fishkind.

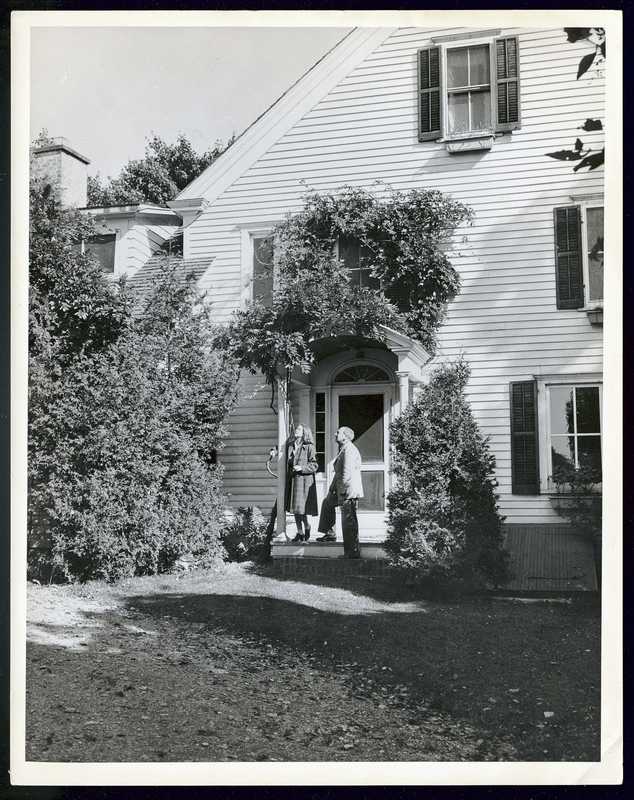

Vincent and Eugen on the front porch of the main house, c. 1945

Photo credit: Edna St. Vincent Millay Society

The main house at Steepletop today

Photo credit: Edna St. Vincent Millay Society

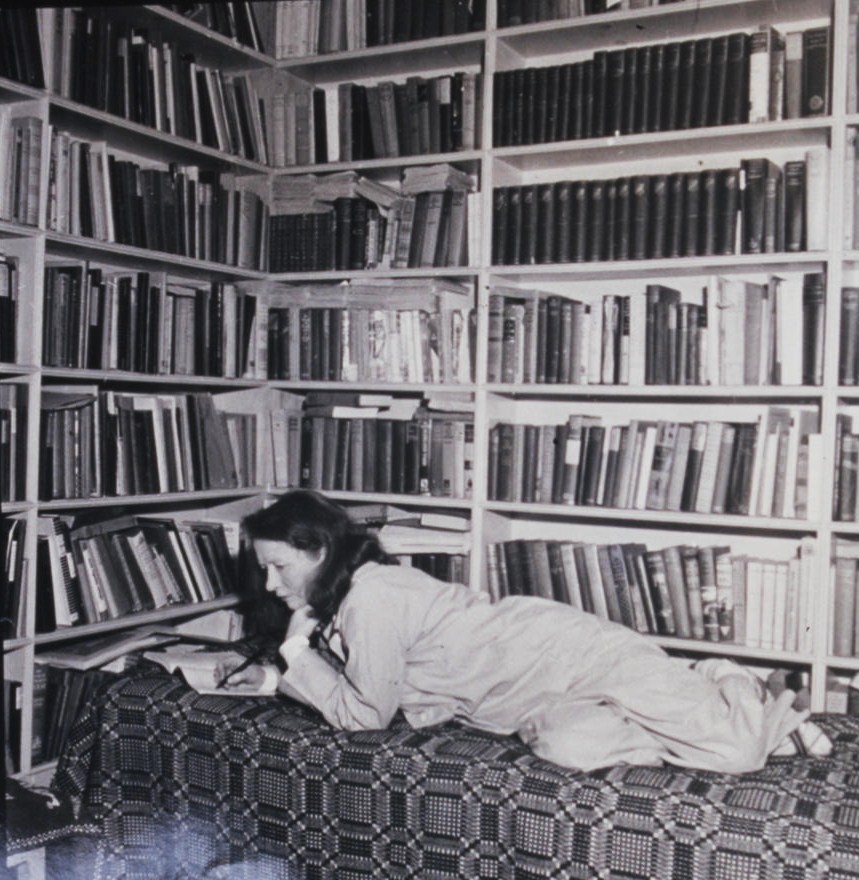

Millay reading in her library at Steepletop, c. 1948 Photo credit: Edna St. Vincent Millay Society

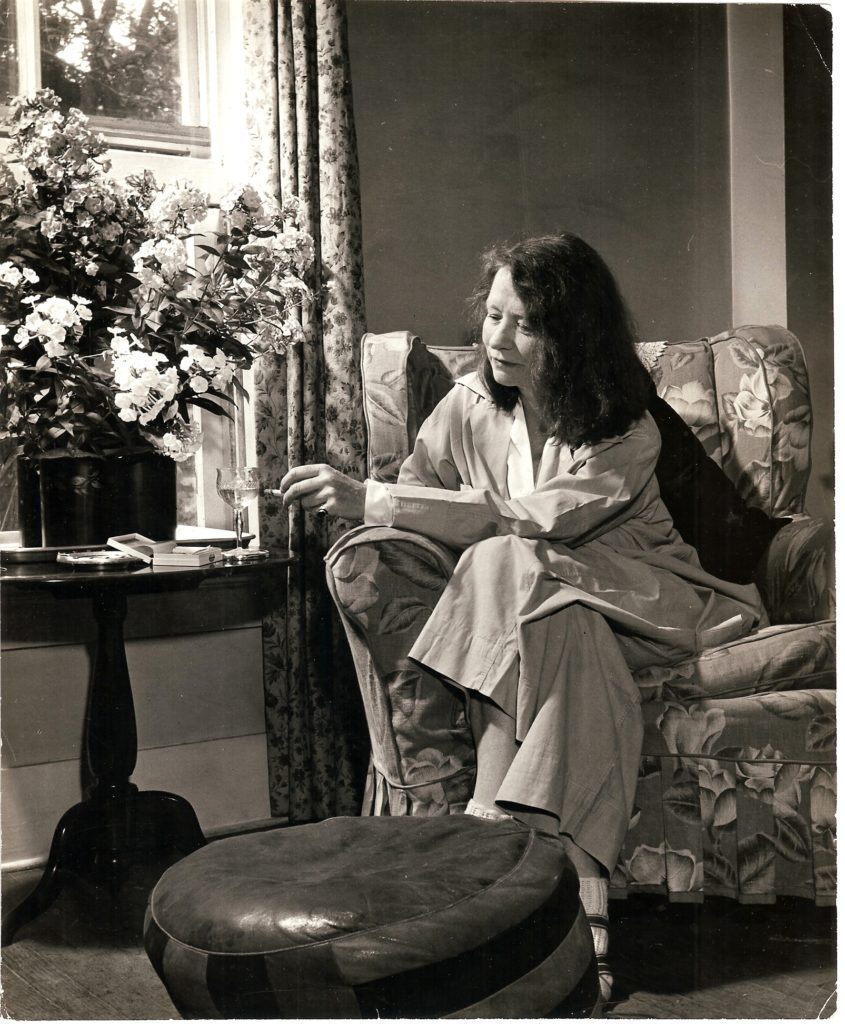

Millay in the “Bird Window Seat” in her withdrawing room, c. 1948

Photo credit: Edna St. Vincent Millay Society

Vincent, Eugen and a friend enjoy a dip in the pool. Bathing suits were prohibited. c. 1938

Photo credit: Edna St. Vincent Millay Society

Below is a transcript for season 1, episode 7 of Someone Lived Here at Edna St Vincent Millay’s home in Austerlitz, New York. If you have any questions about the show or suggestions on how to make it more accessible please reach out at someonelivedhere@gmail.com.

Transcript by Sam Fishkind

Kendra Gaylord: This week, we’re at Steepletop, in Austerlitz, New York. This farm house was the home of Edna St. Vincent Millay. In a tiny cabin behind the house, she would write her poems and plays. She lived here for 25 years, until her unexpected death in the home. Her sister, Norma, moved into Steepletop, leaving everything exactly as Vincent had left it, and so it remains today. Welcome to Someone Lived Here, a podcast, about the places cool people called home. I’m your host, Kendra Gaylord. Every other Monday this season, we have brought you to a cool place in New York and told the complicated stories of the people who once lived there. Today we’re outside a white farmhouse on a steep hill. The home is surrounded by land and white pines. There is a short hilly walk to a blueberry field, forests in-between, and close to the home, a freshwater pool with garden surrounding it. To learn more about how Edna St. Vincent Millay got here and who she was, I spoke with Holly Peppe. She’s the literary executor for Edna St. Vincent Millay, and knows Millay’s work inside and out.

New Speaker: So, Edna St. Vincent Millay, was one of America’s bestselling poets. She was really a virtual rockstar in the 1920s. She was an unlikely candidate for fame. She was born in Rockland, Maine, and she grew up in Camden. She was the eldest of three daughters. Her two sisters were Norma and Kathleen.

Kendra Gaylord: Vincent’s mother, Cora, was a remarkable woman. She divorced her husband in the year 1900, and she raised her three daughters on her own.

New Speaker: So Cora raised these three daughters alone and there was no money to speak of. So they lived in rented homes. They moved from place to place.

Kendra Gaylord: Cora was a traveling nurse who would be gone for weeks at a time, leaving Vincent in charge.

Holly Peppe: The girls were really a unit. It was a little like the Bronte sisters, and Millay was the head of that unit. She was really the mistress of the household, and Cora left her with great deal of responsibility, which really was to keep the house, and to bring up the two daughters.

Kendra Gaylord: But Vincent did a lot more than just look after her sisters.

Holly Peppe: She was extremely talented. She was writing poetry as a very small child. She put a book together for her mother when she was in grade school – and she was also, in high school…she was the editor of the literary magazine and she published poetry from the time she was very small. She really wanted to publish poetry, and there was a magazine called St. Nicholas Magazine, which was a magazine for youth.

Kendra Gaylord: She would submit her poetry under the name E. Vincent Millay so that she wouldn’t be recognized as a girl. She was often published in St. Nicholas Magazine and won prizes, but she could no longer submit to the magazine once she turned 18.

Holly Peppe: After high school, Millay, was desperate because she really wanted to go to college, but there was no money clearly in that family, and it didn’t look like any of the girls would go on to higher education. But Cora one day brought an article home from a newspaper and there was a notice in it about a literary prize; a poetry prize, and the best poem in this contest…the first three poems would win cash prizes, which of course was very attractive to that family. But all of the poems, the top 100 poems chosen as the finalists or as the all runner-ups would be published in a book called “The Lyric Year”, an anthology that was indeed published in 1912. So Millay was already working on a poem called “Renascence”. Now, when she started writing it, she titled it “Renaissance” with the spelling we know, and later when she sent the poem in to be published, one of the editors suggested she changed it to the old spelling and old pronunciation: “Renascence”. So that’s the poem we know today. It’s a famous poem today because Millay did submit that poem to the contest. It was a long poem of rhyming couplets and it was about, of all things, a spiritual awakening that she herself claimed to have had. And it’s extremely sophisticated.

Kendra Gaylord: It was so sophisticated that the editor was surprised after corresponding with Vincent to find out the writer was a 20-year-old-woman. In a letter, he wrote, “no sweet young thing of 20 ever ended a poem precisely where this one ends. It takes a brawny male of 45 to do that.” Vincent was upset when the piece didn’t win the prize, but it was published in “The Lyric Year.” Her sister Norma was waitressing at the Whitehall Inn in Camden, Maine. And one night, there was a talent showcase where the staff would perform for the patrons.

Holly Peppe: Norma asked Millay if she would please recite her poem, her famous poem; for she played a little piano. So she did. She stood up, and she recited “Renascence”. She had little trill in her voice: “All I could see from where I stood / was three long mountains and a wood” – and she mesmerized the audience. And there happened to be a woman in the audience named Caroline Dow, and Caroline Dow was head of the YWCA Training School in New York, and she immediately recognized Millay’s talent, and she asked if she could meet with Millay’s mother. Well, this meeting led to Caroline Dow offering fine support for Millay to attend college. And after looking at several colleges, Millay decided on Vassar. She loved the idea of Vassar, and that is indeed how Millay went to Vassar. There were several wealthy patrons who Caroline Dow had appealed to. She [Millay] was 20 when she went to Vassar, so she was already a famous poet; she was already well known, so she was quite already known among the girls to having a bit of an ego, and to not following the rules when she felt like not following the rules.

Kendra Gaylord: The president of Vassar at the time had once told her that no matter how much she broke the rules, he wouldn’t expel her because he didn’t want to banish Shelley on his hands: referring to the “Frankenstein” writer Mary Shelley. She responded, “on those terms, I think I will continue to live in this hellhole.” Right before graduation, Vincent went to New York City to hear the Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso. She was suspended for leaving campus, and was told she would not be able to graduate. It took a petition signed by 120 members of the faculty for her to get reinstated, and be able to graduate.

Holly Peppe: So after graduation she moved to Greenwich Village, and this is the period of time that we really know most about her people she’s most famous for – I should say, because that’s when she attracted virtually all the male literati of the day. [Laughs] And free love, of course, was in free swing. And for her, experience was the stuff of poetry: experience was fodder for her work. So she broke hearts, I should say, one after another. And Norma joined her in New York, which was really quite wonderful because she wanted Norma to be with her; she didn’t want to be…she thought it would be fun to bring her to New York. And eventually, her mother moved to New York as well. And they shared these apartments; they would go from one apartment to the other. How did she support herself, you might ask? Well, she published poetry in all the popular magazines, but there wasn’t much money in that. So she realized that if she wanted, [she] could write short stories or some of the rather satirical short pieces that Dorothy Parker was writing; that she might make more money. So she did. But she was very covetous of her reputation as a good poet, a careful poet, a craftsperson. She was that so meticulous that she didn’t want to spoil or taint her reputation as a poet. So she adopted a pen-name, Nancy Boyd, and that was her name for prose. And she was often amused that Vanity Fair would publish two poems by Millay and a short story by Nancy Boyd.

Kendra Gaylord: When a book of Nancy Boyd stories came out called “Distressing Dialogues”, you won’t believe who wrote that preface: Edna St. Vincent Millay. Here’s a part of it: “I am no friend of prefaces, but but if there must be one to this book, it should come from me, who was its author’s earliest admirer – I take pleasure in recommending to the public these excellent small satires, from the pen of one in whose work I have a never-failing interest and delight.”

Holly Peppe: So she’s a famous poet in New York. She’s writing poetry, she’s writing a fiction as well. And in 1921 she said in one of her letters that she just was tired. She was tired of that sort of rat race. And yes, and being the famous poet and going from place to place. She decided to go to Europe, and she went with a contract from Vanity Fair who asked her to send these satirical sketches back while she was over there…

Kendra Gaylord: She would spend almost two years IN Europe. She had love affairs with men and women, and traveled through Paris, London, Rome, Budapest, and Vienna. In her time away from the US, she was also homesick, writing letters to her mother and sisters. It was in Europe where she would write “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver”, dedicated to her mother. The poem talks about a son and a mother. They are very poor, and the boy has no clothes. The home is nearly empty, except a harp that nobody would buy…

Kendra Gaylord: “I saw my mother sitting On the one good chair, A light falling on her From I couldn’t tell where, Looking nineteen, And not a day older, And the harp with a woman’s head Leaned against her shoulder. Her thin fingers, moving In the thin, tall strings, Were weav-weav-weaving Wonderful things. Many bright threads, From where I couldn’t see, Were running through the harp-strings Rapidly, And gold threads whistling Through my mother’s hand. I saw the web grow, And the pattern expand. She wove a child’s jacket, And when it was done She laid it on the floor And wove another one. She wove a red cloak So regal to see, “She’s made it for a king’s son,” I said, “and not for me.” But I knew it was for me. She wove a pair of breeches Quicker than that! She wove a pair of boots And a little cocked hat. She wove a pair of mittens, She wove a little blouse, She wove all night In the still, cold house. She sang as she worked, And the harp-strings spoke; Her voice never faltered, And the thread never broke. And when I awoke,— There sat my mother With the harp against her shoulder Looking nineteen And not a day older, A smile about her lips, And a light about her head, And her hands in the harp-strings Frozen dead. And piled up beside her And toppling to the skies, Were the clothes of a king’s son, Just my size.” Soon after the poem was published, her mother Cora would join her in Europe, where they would travel and sight-see. In 1923, both Vinson and her mother came back to the US. She was 31 years old, and received a Pulitzer for that poem dedicated to her mother, “The Harp-Weaver”. And that wasn’t the only life changing thing to happen that year.

Holly Peppe: And she went to a house party thrown by a friend of hers in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. And at this House party there was a game. They played charades, and there was a man there named Eugen Jan Boissevain . And Eugen was a Dutch coffee merchant, very wealthy, very handsome, very dashing. And interestingly, he had been married to a Vassar graduate named Inez Milholland; and Inez was well-known to be a suffragette. She had died of a blood disease very quickly, very young: so Eugen was a widower. He was at this party, and he was really put-together by Floyd, Dell and a few of the others there who fixed them up, and they played a married couple sort of of a bumbling, country-bumpkin kind of couple who are coming to New York; going to New York on the train, going to the city on the train – and she was the wife, and he was a husband and sure enough, as several of the people wrote later: “it was like watching people fall in love”. So very few months after that game of charade, they decided to be married, and part of the reason they want to be married so quickly is that Millay wasn’t well. She always had intestinal issues and she needed surgery.

Kendra Gaylord: Almost immediately after the wedding, Eugen drove Vincent to Manhattan for surgery. She recovered, and the two would live for two years in a famous Manhattan House, 75 and 1/2 Bedford Street. It’s known for being “the skinniest house in New York”, measuring nine feet and six inches wide. Vincent was five feet tall, so that’s less than two Millays. They went on a belated honeymoon around the world for eight and a half months. And when they returned, Millay didn’t think she could write in the city anymore, which brings us to our main character.

Holly Peppe: So she was reading the New York Times one day, and she found an ad in the New York Times for a farm – an abandoned berry farm in Austerlitz, New York for $9,000 for 435 acres. And she right away she said, “that’s the place – this could be it!” And she and Eugen came up and saw the place, and they purchased it right away. Now the house was completely run-down across the road. There was a farm called the Bailey Farm. It’s 300 acres and soon after they purchased Steepletop, they decided to buy the land across the way so they would own the whole mountaintop, which they did. So this was a farmhouse, there were various outbuildings and she named the place Steepletop, because of Steeplebush, the plant/the flower that grows on the fields and meadows here; is still here. It did then. And it does now.

Kendra Gaylord: We’re now going to meet Mark O’Berski. He’s the Vice President of the Millay Society. He’s going to walk us through the home and property, and show us where and how Edna St. Vincent Millay lived. And we’re going to start in my favorite place: the gardens

Mark O’Berski: Millay created outdoor rooms, so – four that were used for entertaining or strolling. And originally all of these garden gates were connected by a Berkshire hurdle fence.

Kendra Gaylord: I looked up a Berkshire hurdle fence and to me it looks just like a nice country fence.

Mark O’Berski: When they bought the property in 1925, the property was really run-,down and there were two barns here and another barn over here to the left – and you can see the remnants of the stone wall of the foundation there as well. They tore the barns down, but left the stone walls up; the foundations because of all her travels throughout Europe, she was enamored of all the rock wall gardens that you would see in Europe and particularly throughout England. And she wanted to recreate that feel here at Steepletop. So within “the ruins”; and she called that because it was the ruins of the barn, there are several rooms, so we’ll pretend we’re walking, and just as they would have done through the gate…

Kendra Gaylord: [The gate came down a long time ago, so let’s just pretend you hear the creaking.]

Mark O’Berski: So what we’re overlooking now, this is the Pergola bar and this – the pictures we have of them sitting at the bar out here…is just wonderful. So they would hang out here; Eugen was the bartender, he would behind the bar here, making cocktails for everybody and they would all sit around the bar, they’d go for a swim, they’d come back to get a drink. And then all along this wall here, because it’s a rock wall and very conducive to growing plants, she would have her hollyhocks and very much the plants that you see here today. And then over here is the swimming pool. So, this is a spring-fed pool. It’s rather ingenious. They put it in themselves and up on the mountain and back of the visitor’s center, there is a cistern up there. There’s a running stream up at the top of the mountain, and they would collect the water in the cistern, and then they put in pipes, a series of pipes; underground that fed that went all the way down the hill, and because of the gravity was so strong, it went down under the hill, under the road, across to fill the swimming pool. And it was constantly flowing. Water in, water out, water in, water out so that it always kept clean, fresh spring water and would also feed these two fountains. And then it ended at the bar. There’s a spigot at the bar so that Eugen would have fresh water at the bar!

Kendra Gaylord: They even had two dressing rooms, one for men, and one for women, built within the trees. But the pool had one rule: no bathing suits allowed. We’re now going to go inside to what was once two parlors.

Mark O’Berski: So this is the withdrawing room. So we’ll take a walk in. And what you see that is very unusual for a Victorian farmhouse, is the size of this room is enormous. It used to be two rooms, two separate rooms, as there would have been in a Victorian house, two front parlors. And they had the wall removed so that Millay had room for two grand pianos. So, because she liked to play duets with friends, she has two grand pianos in the room. So over here, this is Millay’s piano: It’s a Steinway from 1925. No one was allowed to play this except Millay.

Kendra Gaylord: This room isn’t that big. And two grand pianos take up most of it, and in the other corner of the room are couches and a fireplace. There was also a little chair by the window that meant a lot to Vincent.

Mark O’Berski: This chair that we see in the corner – it’s called the “bird window seat”, because that’s where Millay would often sit. She kept a bird journal next to her, she loved birds, and that window was always open. And if you look over here, you’ll see that there was a bird feeder place directly outside of the window, and she would have the window open here with a little tray of bird seed, so that the birds would then come into her room; so that she could view them, and she would take notes in her journal. We still have that journal today, with all of those notes and it’s really very funny because she argues with the writer of the book, where the writer will say, “this is a rather ordinary bird”, and she writes, “excuse me, this isn’t ordinary bird, this is quite a lovely bird! He has a beautiful song.”

Kendra Gaylord: And after walking through the garden a little bit here, I can agree the birds here do have a beautiful song. A lot of what Vincent loves so much about this home was the nature that reminded her of Maine. She planted all the tall white pines because when they blew in the wind, it sounded like the ocean. She was constantly corresponding with her mother in Maine. Cora also wrote poetry, and in January, 1931 – Cora St. Vincent, a short poem:

Kendra Gaylord: “My little Mountain-Laurel trees So sturdy in a row; I loved the ones who set you out And wanted you to grow; Of course I love my other trees So stately and so tall – But I loved some Mountain Laurel trees When I was very small.”

Kendra Gaylord: In less than a week, Cora would die in Maine. They drove her body back to Steepletop and buried her in the mountain laurel grove. Vincent wrote poems about her mother, but the one I love most was written 10 years after her death:

Kendra Gaylord: “The courage that my mother had Went with her, and is with her still: Rock from New England quarried; Now granite in a granite hill. The golden brooch my mother wore She left behind for me to wear; I have no thing I treasure more: Yet, it is something I could spare. Oh, if instead she’d left to me The thing she took into the grave!— That courage like a rock, which she Has no more need of, and I have.”

Kendra Gaylord: After illnesses and accidents, including falling out of a moving car, Vincent was prescribed morphine and became addicted. There are notes from her sister Norma expressing her worry. This is also happening around 1939, when World War II had just begun. Despite being a pacifist in the past, she felt that the US had a responsibility to enter. She published a book of poetry called “Make Bright the Arrows”. Reviews at the time called it propaganda and her reputation in the poetry world was really damaged. That was the start of an extremely difficult decade. Her sister Kathleen died in 1943, followed by her longtime editor, and then her closest friend Arthur Ficke. A few more years would pass, and then Eugen, her husband, died suddenly in 1949,.Vincent grieved alone in the home. Within a year, Vincent died. Her sister Norma would move into the home and be its steward, living there even longer than Vinson ever had, but never making it her own. I now want to go upstairs to the rooms where you can feel the energy of Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Mark O’Berski: This is Millay’s suite. Really. This is the bedroom. She kept a notepad next to her bed so that she could…when she’d wake up in the middle of the night with thoughts or ideas,she could jot them down and then her secretary would come here in the morning and take dictation and take her notes. On her dresser, when Eugen died in 1949, she brought his dresser scarf from his bedroom and placed it here. So those are his initials on there; and the linen dresser scarf. And this is his letter opener, also with his initials. And that is a portrait of Eugen when he was a little boy; he’s about six years old there. And on the day he died, she inserted her own photograph in the frame and it’s just been there ever since. And then this is her dresser, her vanity. So these are all her personal care items and her jewelry box. And when Norma lived here, Norma lived around her sister’s things. So I’ll show you that what we found on this vanity [hinge creaks], this is a shoe box that Norma kept on the vanity with her things in it, her cosmetics, so that she didn’t, you know, bother her sister’s items.

Kendra Gaylord: We’re now gonna move on to the bathroom. It’s beautiful and simple, with pink walls and white bathroom fixtures. But the best part are these white towels monogrammed with her initials: E. S. T. V. M.

Mark O’Berski: The scale over here in the corner is a relic, but it’s still weighs perfectly accurate. And it is the weight that Millay was when she died. So she was about 98 pounds when she died. And these are actually Norma’s, these gowns… These, they’re not really gowns – they’re dramatic caftans that she liked to wear about. And we just kept these here for visitors so that they could see how Norma used this room. She hung all of her own clothes on this shower rack so that she didn’t disturb all of her sister’s gowns in the closets. So Norma put her things hanging here, and she used the bathroom and Eugen’s suite when she needed to take a bath or whatever, she wouldn’t even disturb this bathroom. So then we’ll come into the room that is really the heart and soul of Steepletop. And this is Millay’s personal library. So, you see here a great many volumes of books. There are over 3000 volumes in here, and the room is really organized into sections. So this whole section in this corner, all of the reference books and what you see here, you’ll see books in French, Spanish, Latin, Greek…Millay was fluent in seven languages, and she would really use these books to study. And then over here, these are mostly novels. And then over here in the corner, these are all the classics. So you have Shakespeare, and then this wall is really a lot of human interest, human studies, women’s books. On women’s rights.

Kendra Gaylord: There’s a desk in one corner, a bed-like couch tucked among the shelves, and then a comfy chair in another corner. There’s also a sign hanging from the ceiling that says “SILENCE”. Vincent rarely let anyone in this room, so it feels almost like you’re trespassing to be in it. We’re now going to head down the stairs, which were unfortunately the last place Edna St. Vincent Millay was alive.

Mark O’Berski: You see here, these are the stairs at Millay fell down, and her body lay at the base of them on the landing. She had left a note that night to her housekeeper, on the kitchen table and the note said, “Oh, you know, I’ve been up all night, working, I’m extremely tired. It’s 5:30 AM I’m going to bed. E.S.T.V.M.” And then it wasn’t until 3 o’clock in the afternoon when John Penny came into lay the fires for the day; for the evening that he saw her laying lifeless on the floor. The official coroner’s report said that it was a heart attack. So, she could have had a heart attack and fell and broke her neck or she could have fallen and had the heart attack. We just don’t know.

Kendra Gaylord: I asked Mark to walk me out to where the Millay family resides now. We walked through blueberry fields with those tiny, wild blueberries that remind me of Maine. Then through some high grass and then a mossy path in the forest. At the end of the path is a small mountain laurel, and under it is Cora Millay, with her daughters, Vincent and Norma right nearby. I wish I could tell you to visit Steepletop tomorrow, but unfortunately the property had to close to the public last year. Steepletop doesn’t have an endowment. They’re now looking for donations, or organizations that could help preserve this place for the long-term. I hope they have success, because I just left and I already want to go back. Thank you so much for listening to the first season of Someone Lived Here. If you liked the show, I’d love to read your review on Apple podcasts. We’ll be back with new episodes in the Spring of 2020. You can subscribe to the podcast so you don’t miss it. Thank you to Holly and Mark and the entire Millay Society. Thank you to Sam Fishkind who has done our transcriptions on the website. Music is by Tim Cahill and podcast artwork is by Ben Kirk. If you have any recommendations for next season, send us an email and someonelivedhere@gmail.com.