This home garden is where 100s of lilacs were created

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Email | Patreon | Transcript Below

In this episode of Someone Lived Here, Kendra brings you to the Hulda Klager Lilac Gardens in Woodland, Washington. The home was built by Hulda’s family, The Thiel’s in 1889. Hulda Klager would purchase the home and move in in her 40s.

She became interested in the work of Luther Burbank, a horticulturist and hybridized. She had been inspired by the book New Creations in Plant Life by William Sumner Harwood, which detailed Luther Burbanks process. Hulda Klager began her own experiments with hybridization: first with apples, then lilacs. Behind the house is a large garden filled with lilacs, many of which were Hulda’s creations.

This episode wouldn’t be possible without the Hulda Klager Lilac Garden. Mari Ripp, the executive director, made this whole recording possible. Judy Card, Debbie Elliott, Barbara Harlan, and Mari Ripp guided us through the home and property. The historic talk was put on by the Hulda Klager Lilac Garden, the Woodland Historical Museum, and the Lelooska Foundation. It was moderated by Erin Thoeny and recorded by Keith Bellisle. Thank you to Mary Jo Kellar, Fran and Kirk Northcut, and Jon Drury for their stories.

Images from the day of the interview were taken by Ada Horne. Tim Cahill created our music. You can find a full transcript of this episode below the photos.

Below is a transcript for S3E7 of Someone Lived Here at The Hulda Klager Lilac Gardens and House in Woodland, Washington. If you have any questions about the show or suggestions on how to make it more accessible please reach out at someonelivedhere@gmail.com.

Kendra Gaylord:

This week we’re at the Hulda Klager Lilac Gardens in Woodland Washington. The grounds and the house were owned by Hulda Klager, also known as the Lilac Lady. It was here that she would host Lilac Days, which brought thousands to her door, wanting to see her springtime lilacs, and when I say her lilacs, I mean hers. She created her own, originating over a hundred new cultivars through hybridization. A number of them still exist today in the sweet-smelling backyard of the Hulda Klager house.

Welcome to Someone Lived Here, a podcast about the places people called home. I’m your host, Kendra Gaylord.

We’re walking down a path made up of red pavers, but it’s impossible to look down at the ground when you’re walking through a garden like this. There are trees and shrubs everywhere. There aren’t many lilacs in this front area, instead, yellow azaleas, pink rhododendrons, camellia blooms starting to fall off their branches. And nestled within all these flowering plants, there’s a white Victorian farmhouse with a front gable and a porch with lace-like brackets. The front door has a glass window with squares of colored glass around its edge.

Hulda Klager was born May 10th, 1863 in Germany. Her and her family moved to the United States when she was two, and to Woodland when she was a young teen. Once she moved to Woodland, her birthday and lilac season would forever line up. This Victorian farmhouse was built in 1889 by Hulda’s father. At that time, she was 26 years old with three daughters and a son on the way, living with her husband, Frank Klager, in a house in town. He was a dairyman. It was after her parents’ death when she would make the house her own, and the garden she built would reach celebrity status.

You can’t see many lilacs in front, but if you follow along the right side of the house on that same red path, you’ll see plenty of them. The back porch is steps away from a large potting shed. To the right is a barn that’s been turned into a museum. Right next to it, a windmill and a water tower. In between all these buildings are tall, lilac bushes with long branches that intertwine and reach towards each other, many with name tags in the ground like this one called My Favorite. I can see why Hulda would name it that. In the lilac world it would be called Magenta, but to the untrained eye, it’s just a beautiful purple.

A lilac is made up of many little flowers all clumped closely together at the end of a branch in a cone-like shape. The closer you get to the lilac, the more you notice the scent. A smell so sweet it’s almost thick. While most lilacs you’ve seen are single layers of petals, my favorite is a double, giving it a frilly appearance. To understand how this lilac came to be, we should go inside to where it all started. The back porch leads to a back door, which leads to the kitchen where we’re going to talk to Judy Card. She’s running the tour today and has been researching and compiling this family’s history for years.

Judy Card:

The glass, all original-

Kendra Gaylord:

Judy is talking about the windows because when you first enter this room, your main focus is just how bright it is.

Judy Card:

But you can see, looking at this one, glass is liquid.

Kendra Gaylord:

Yes.

Judy Card:

So you can see there that that is running, and I believe over the sink it’s running a bit.

Kendra Gaylord:

That wavy glass is classic of older homes with their original windows, but right next to that window is a built-in cabinet I’ve never seen before.

Judy Card:

We have what I call a pie safe here in the end. Maybe you’re not familiar with that. See if I can put it in here. So the shelving is slatted for circulation. It’s open to the outside and they would’ve had a tin base here for putting blocked ice to keep it cool.

Kendra Gaylord:

From the outside, it looks just like a cabinet, and the way it functions is sort of in between a pie safe and an ice box. They’re sometimes referred to as California coolers or cooler cabinets, and they were common in the Western United States. It was ideal for keeping baked goods and leftovers cool. One of the baked goods that probably found a home in this cabinet were apple cakes and pies with a very special ingredient that was inspired by this book.

Judy Card:

New Creations in Plant Life by the author, W.S. Harwood, but it was about the work and methods of Luther Burbank.

Kendra Gaylord:

Luther Burbank was a horticulturalist and an early innovator in the modern American agricultural science movement. You might not know him, but you’ve certainly tasted his work. He developed the Russet potato at 24, followed by a long career creating hundreds of new varieties of fruits, flowers, vegetables, grains and grasses. This book captured Hulda’s interest and she began her own experimentation.

Judy Card:

Her own first tests began with an apple tree, crossing the milder Wolf River apple with a sour, juicy, wild Bismarck. She was successful at producing larger fruit that took less time to pair.

Kendra Gaylord:

Apples were just the beginning, instead shifting her focus to lilacs. At 42, she started her journey hybridizing lilacs, and in five years she had created 14 new cultivars. That was just the start. Over her lifetime, she created a hundred cultivars. In one season, she might be observing 300 seedlings, and the place that observation happened is just a room away.

From the kitchen, you walk through a big living room that was once split into two rooms. As Hulda got older and the stairs became more difficult, she would turn one of them into her bedroom, making her even closer to the little conservatory tucked onto the left side of the house.

It’s a step down to the small conservatory, which isn’t much bigger than a twin-size bed. It looks like a closed-off part of the porch with floor-to-ceiling windows on the south side of the house. Across all of these windows are rows and rows of shelves. Right now they’re mostly spider plants and Christmas cactuses, but for Hulda, these would’ve been filled with her lilac starts.

Mari Ripp, the executive director of the Hulda Klager Lilac Gardens is going to show us some of the things in this room.

Mari Ripp:

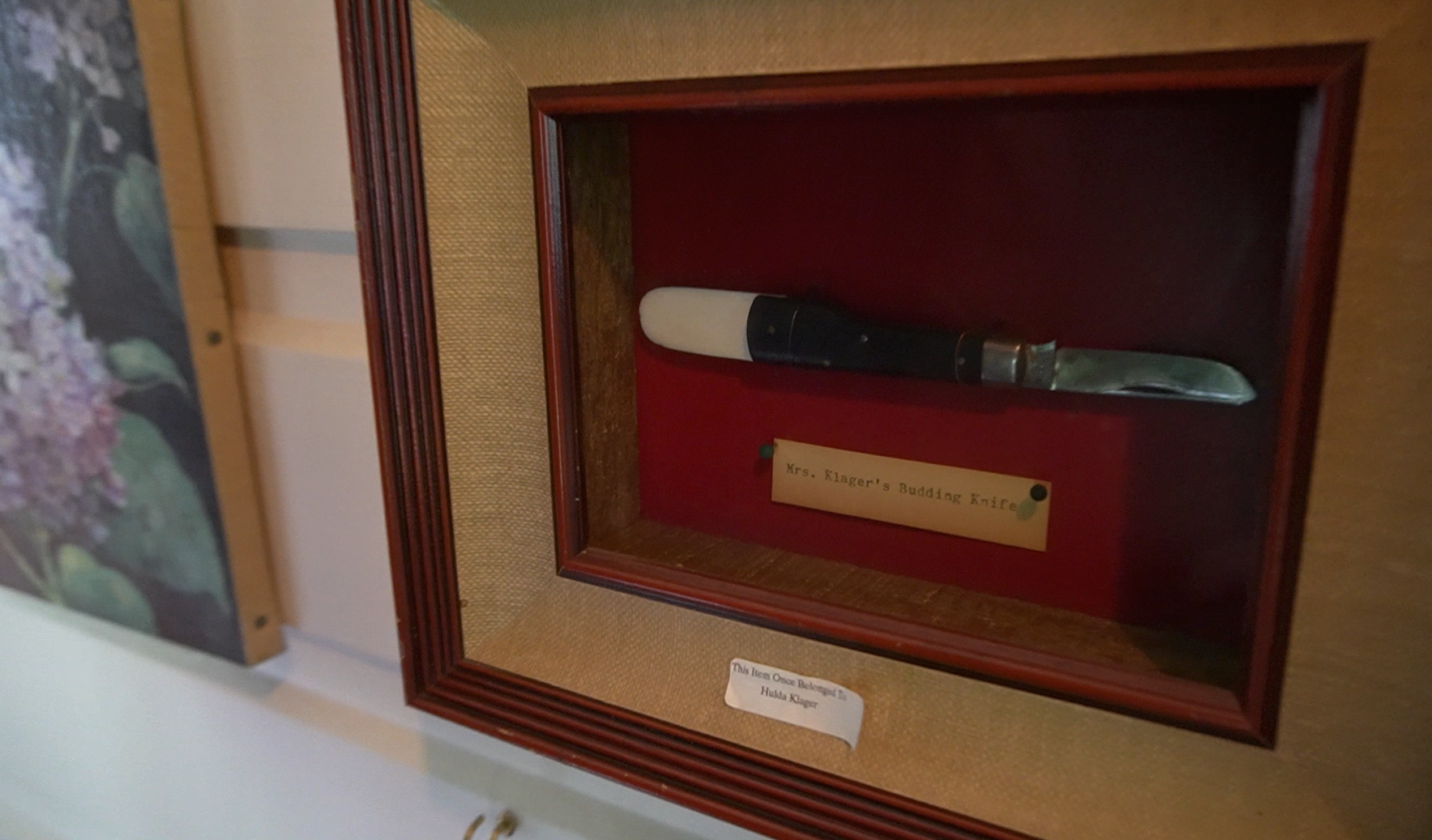

And then over here is the grafting knife that was used by Hulda. She used that in her cultivation of lilacs and also for her apples in the early days before she moved onto lilacs.

Kendra Gaylord:

I haven’t seen a knife like this before. It’s framed on the wall in a red shadow box with a black handle, and opposite the blade is a bark lifter that looks to be made of bone. It’s paired with a small typewritten sign, Mrs. Klager’s budding knife.

Mari Ripp:

And then her hat up there, there’s her garden hat and her hoe, which you’ll see her holding the hoe in some of the pictures and stuff, and in the potting shed outside, she also has a number of her gardening tools that we have on display out there.

This is kind of interesting here. This we think would’ve been one of her drying racks and she could have been holding many different things on that, but probably herbs and seeds and things like that, she would’ve used to hold that.

Kendra Gaylord:

That drying rack is kind of hard to explain, but I’ll give it a shot. It’s mounted to the wall with many dowels that hang down, but if you want to use it, you lift the dowel to horizontal and press it in, which locks it in place. It couldn’t hold much weight, but I’m sure many a seedling dried out here. There are a few other things in this room, A postage stamp quilt made by Hulda using tiny little squares of fabric and then a chair with magazines profiling Hulda and her garden. After 20 years working on her lilacs, her work was being memorialized in print like Better Home and Gardens in 1928 with the title, It’s Always Lilac Time In This Garden. It was in this article where she described the endurance required.

“At first, I hadn’t learned the lesson of patience and I would be disappointed when the blossoms weren’t what I expected, but now if I got one out of 400 worth saving, I rejoice.”

Hulda initially started with three French lilacs of different colors. She went on to describe her process and how it evolved.

“I tried dozens of different combinations that first year, just everything that came into mind, and I worked very carefully too, using a small paintbrush to put the pollen on the stigma. After I had carefully examined the pistil through a magnifying glass to see that it was receptive and that it had not already been fertilized, then I covered the pollinated blossom with a paper bag to protect it from insects. Now I can tell at a glance the condition of a pistil. I’ve discarded the paintbrush. For now, I rub the blossom with the pollen I want to use right onto the pistil. Paper bags aren’t essential either. I found that out too.”

At the end of the article, the writer describes Lilac Day when Hulda opened her garden to community. “She moves about her beautiful grounds going graciously from one guest to another, answering their eager questions.”

A local newspaper wrote about the 1928 Lilac Day. “Lilac Day at Mrs. Hulda Klager’s lilac garden brought the largest number of people that have yet attended these events. In the afternoon, account showed 400 cars parked there in an hour. It is estimated that at least 2,500 people were there for the day.”

Hulda Klager would sell her lilacs to people who came and visited. The Better Home and Garden article mentioned how she rarely would sell her lilacs to nurseries, instead preferring to sell to people who came to visit her garden. Now, Lilac Day has become Lilac Days and takes place the three weeks leading to Mother’s Day weekend, it’s when the lilacs are in full bloom and often when there are storytelling events. We came during these Lilac Days, which meant we also got to hear from longtime residents of Woodland who had met Hulda Klager, like Mary Jo Keller.

Mary Jo Kellar:

My name is Mary Jo, and that’s my first name. Kellar K-E-L-L-A-R. But my maiden name was Leathers, and there’s history on the Leather side.

Way back, well, it was before the ’48 flood, my grandfather was interested in how Hulda Klager was doing her lilac starts, her hybridizing. And when I was probably six or seven, my brother Craig was two years younger, my grandfather brought us down here to see Hulda’s garden and what she was doing with her hybridizing. And just before we got down here, grandfather turned to my brother, mainly because he was kind of a stinker, and he shook his finger at us, whilst driving with the other hand. And he says, “You do not play in Hulda’s garden.” And I don’t see the picture of Hulda standing with the hoe. It’s over there. This is what we saw when we got down here. We kids saw Hulda with her hoe. She was out in the garden when we got here and she scared us for that, and we didn’t play in Hulda’s Garden.

Kendra Gaylord:

There’s a few photos on the wall that help explain what Mary Jo remembers. Hulda is in her eighties, in a black dress and glasses. She isn’t smiling. She has one hoe in each hand and she looks ready to use them. The biggest photo on the wall shows Hulda from a distance. She’s looking to the left of the camera, again in her black dress. There’s a black cane standing upright where she shoved it into the dirt. Instead of leaning on her cane, she’s leaning on her shovel. In front of her is a small lilac sapling.

Mary Jo Kellar:

So she later took us into the house and through the back door, and she has what? I don’t know, it’s called the sunroom now or the conservatory, but it used to be where she started all her plants. And so she took my grandfather in the back there, and I remember peeking around the corner. Craig and I didn’t go in there. We were out in the living room, but I remember her china cabinet and she had all these beautiful dishes and things too, but we didn’t play in the house either.

Kendra Gaylord:

Now, when Mary Jo mentioned meeting Hulda, she said this was before the flood. The 1948 Columbia River flood is a big tie marker for this area and for this property.

Mary Jo Kellar:

Well, we had a small dairy herd then, and I was just about seven. Two things stand out. One, our house had been built with a high foundation so that we did not get water in our house, and it was right along the river over here. Most of the water came from the dikes and through the town and out our way, and we were a little higher, but we had to do something with those dairy cows. And I can’t remember. I think my dad took them up to higher ground place that he knew. The boils and the dikes started to break first down here and the water spread this way. And then farther over here from the Columbia, the boil started on the dikes there and burst. And Kirk remembers more about the flooding. They had a lot more water, but I remember going around in a rowboat. We thought that was great fun, we kids.

But the worst part that I remember as a kid, was the aftermath, when the whole town of Woodland had to line up over here where Lewis River Motors was, and for three Fridays in a row, we had to get cholera shots. And I remember the kids and the lines, parents hanging onto those hands so the kids couldn’t run, but the whole town was lined up from all down where the access road is to Safeway. We got shots every Friday.

Kendra Gaylord:

Mary Jo mentioned Kirk’s family having a lot more flooding. Kirk Northcut was also on this panel of speakers, so we got to hear his perspective.

Kirk Northcut:

Morning that we moved out, I went with my dad up on the dike, and he measured the water like 12 inches from coming over the dike at that time. The dairymen on the bottoms, they all got together and they started moving everybody’s cows out. My dad had milked about a hundred cows at the time. Places to bring them got very short. I know we lived in a machine shed for I think it was a hundred days. We had several buildings, all the buildings left. We had approximately 25 to 30 feet of water on our property.

Erin Thoeny:

So they physically floated away.

Kirk Northcut:

Yes. Our house ended up in the middle of Capels Road. County had to build a road around it until my dad got the house tore down to get it out of there.

Kendra Gaylord:

As you can hear, it was a really destructive flood. Kirk’s family farm was about a mile away from Hulda’s. Back in the house, I asked Judy for more information.

Oh, and then the flood in 1948, did that affect this house as well?

Judy Card:

Even after the house was raised, because there were floods in 1894, 1922, 1933. 1948, it came up to about our knees, 20 inches. They had to replace four panels on the kitchen cabinets, and I think that’s the only damage. These are the original floors.

Kendra Gaylord:

Resilient.

Judy Card:

Yes, good quality.

Kendra Gaylord:

There’s no signs of flooding in the house except if you open the closet underneath the stairs, you’ll see a water line on the door right around knee height. That’s how high the water got, and that’s on a foundation at least three feet off the ground. The lilacs in her garden didn’t fare well. Hulda had just turned 85. The flood took most of her lilacs. Only the oldest shrubs and trees stayed standing. The work that had been her driving force for over 40 years was washed away. It had been her companion through the loss of two of her daughters and her husband. She had lilacs named after them and all her family members. She had dedicated and named lilacs after neighboring cities, and now so many of her cultivars were gone.

But she had been gifting and selling and dedicating those lilacs to the surrounding communities for decades. Lilac days had spread her lilacs all over. So at 85 when she decided she would get back to work in her lilac garden, that community was happy to return the favor. The photos I mentioned of Hulda in her black dress with her shovel, were taken after the flood and it looks nothing like the previous photos from those articles. The ground looks uneven and almost sandy and the former shrubs are now lifeless sticks. Plants and starts of her lilacs were brought back to where they were invented. Mary Jo’s grandfather was one of the Woodland residents who returned some of the lilacs he had gotten over the years. Everything was fixed up. And now we can just see that small hint of the flood on this closet door under the stairs.

As we continue to walk towards the front of the house, there’s a parlor off the entryway. For Lilac Days, they have a volunteer pianist who would be playing songs on the family’s upright piano, if this recording didn’t require silence. Is it nice to play this piano or is it a little finicky?

Barbara Harlan:

Well, you consider it’s over a hundred years old, and so no, I mean material things are going to deteriorate. But it’s nice for what it is. It really is. So it’s been fun to play on it and it just fits with the room and wonderful.

Kendra Gaylord:

The room has lots of Victorian furniture, small chairs, sofas, places for people to sit. It has a door that goes directly outside, which is sometimes referred to as a coffin door. Since most funerals took place in the home, the separate door is believed to make it easier to avoid awkward angles with the coffin.

The stairs are across from the parlor. As you walk up them, there are photos of Hulda and her family hung on the walls. Upstairs there are three main rooms. The biggest one is set up as Hulda’s bedroom with her original bed and dresser set, all painted white. The room feels really bright and airy with lace curtains and a blue and white quilt she made at the foot of the bed.

On the wall in here is a beautiful wallpaper with a white background and bluish roses trailing down in rows. This wouldn’t have been original wallpaper, but was brought in when the home and gardens were taken over by the Hulda Klager Lilac Society in 1976. Mary Jo had the best description of the people who made up this group.

Mary Jo Kellar:

They were all type A personalities. They were determined to save it though, and they were very historically minded and we were all friends, and my grandparents were all friends with these in that generation too. But they were a force and they were determined to save this piece, and I can’t describe it any other way. One of the ladies had some land that I am pretty sure that they did some swapping with the family so that they could keep this place in the family that swapped the other piece.

Kendra Gaylord:

Hulda had died a decade after the flood, at 96. She saw her lilac garden come back together. The home was lived in by members of the family after her death and seemed destined for development until those trades were put in place by members of this group. Her lilacs were saved and the garden began a new transformation. Kirk Northcut is sitting next to his wife, Fran Northcut, the former president of the group. He describes how it was set up in earlier days.

Kirk Northcut:

We’d plant young lilacs out and people would come in, they’d walk up and down the rows and see what lilac they want. And so if I’d be with them, they’d dig it up, they’d bring them to the potting shed. One person would take it and put it in a piece of newspaper. The job I had, was take that and put it in a bag, put a bunch of wet dirt and stuff on it and put it in a sack and give back to them. And they would pay for the lilac and they’d go out the door. That’s why there’s two doors in the potting shed, in and out. And that’s the way we did it at that time. I had a better idea, and a friend tried several different ways of keeping it going, and we come up with putting the pavers in to make it easy for everybody. Well, I don’t know if anybody knows, but there is 55,000 pavers out there. I think I could vouch for each one of them.

Erin Thoeny:

Did you lay them all?

Kirk Northcut:

Not all of them, but I was in on it. We had a lot of good volunteers.

Kendra Gaylord:

I think it’s time we follow those red pavers into the back of the property that is just brimming with lilacs. Mari’s going to guide us through.

Mari Ripp:

Got good shoes?

Kendra Gaylord:

Yes

Mari Ripp:

So this is a Frank Klager. That’s another Frank Klager to our right, the dark purple. Very beautiful. I call it a deep purple and it’s a single flower petal, but there’s really a lot of them on a cluster. It blooms about middle of the season and it’s a favorite of many of our guests.

Kendra Gaylord:

And that one that’s kind of weeping into the area.

Mari Ripp:

That’s a Frank too. Yes. This kind of whole grove is a Frank and it’s going to continue on over to here.

Kendra Gaylord:

Oh, and are these the ones for the cities?

Mari Ripp:

Yeah. So here’s City of Gresham. Pink Elizabeth was named after her daughter. This is actually classified as a pink, although to me it looks kind of a pink lavender. It’s a single and it’s a middle blooming lilac. Yeah. This is the kind of lilac that you’re going to think about when you think of a lilac. You’re going to think of the Pink Elizabeth.

Kendra Gaylord:

I also think whenever I see a lilac for the rest of my life, I’m going to think of Hulda in this place. Mary Jo put into words what makes this place so special.

Mary Jo Kellar:

I think the history and the progression of people building on that history and keeping Hulda’s legacy up front. These pictures are Hulda’s family, Hulda herself. She was a strong woman. She came back after a lot of problems and disasters in her family and her personal life. People helped her because they believed in what she had been doing. I look at my grandfather and he got all this information with the plantings and the propagation and techniques, and it is just a legacy that continues to go on.

Kendra Gaylord:

Coming here, it’s easy to see Hulda’s legacy. She was so resolute in her interest. She shared her lilacs and her knowledge to those who cared. And in turn, she found a community so proud to call her their’s, ready to return what she had given them for the chance to be part of the special place she created. She became known as the Lilac Lady because she showed her passion so intently and unabashedly. Hulda Klager outlived all her children. She’s now buried with her family in the Memorial Cemetery under a lilac tree.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Someone Lived Here. I’ll be giving some casual updates after these credits. Thank you to Ada Horne who assisted me in filming and photographing this podcast episode. You can see their photos on Someone Lived Here.com. Thank you to Mari Ripp, the executive director who made this whole recording possible. Thank you to Judy Card, Debbie Elliott, Barbara Harlan, along with Mari Ripp for guiding us through the home and property. The historic talk was put on by Hulda Klager Lilac Garden, the Woodland Historical museum and the Lelooska Foundation. It was moderated by Erin Thoeny and recorded by Keith Bellisle. Thank you to Mary Jo Kellar, Fran and Kirk Northcut and Jon Drury for their stories. Tim Cahill created our music.

And now for some updates, I know it’s been about a year since the last episode, and that honestly is what you should expect from this podcast. I will still continue making Someone Lived Here episodes, but probably at the quantity of one or two a year. I’m now posting to YouTube every month. These are deep dives into topics I think you’d probably like. I recently did a video on Mail Order Sears Houses, and one on the History of Water Towers.

I do have big dreams for Someone Lived Here, and I hope I can make those happen someday. But in the present, YouTube is what is giving me consistency and cash flow. So if you’d like to join me over there, it would be greatly appreciated. The Patreon for Someone Lived here has morphed into the Kendra Gaylord Patreon. Supporting it still gets you access to every bonus episode of Someone Lived Here. Now, it just also gives you the perk of monthly videos from me. I’m also testing out a newsletter through Patreon, so even if you aren’t able to financially subscribe, you can still get a monthly update from me for free. I know a lot of you have been here since the very early days of this podcast, and I appreciate it so much. I hope these episodes bring you as much joy as they bring me.