Explore the home of architect Theodate Pope Riddle

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Transcript | Email

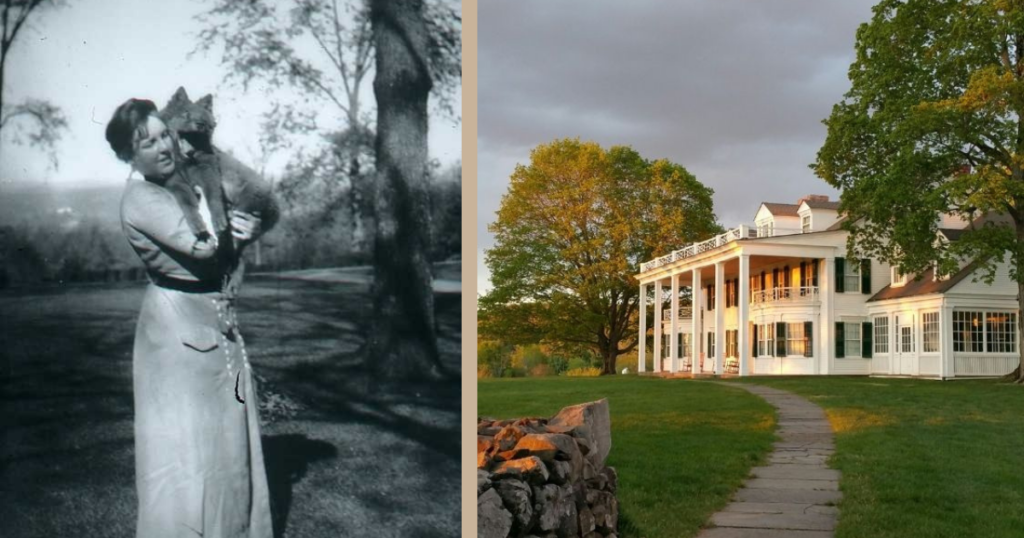

In the first episode of season 3, Kendra brings you to the Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington, Connecticut. Theodate Pope Riddle designed this home, her first architectural project, as a retirement home for her parents. Throughout the episode, we learn about her close friendship with Mary Hillard, her fixation on communicating with the dead, and her near-death experience as a survivor of the sinking of the Lusitania.

Theodate’s father, Alfred Pope, was Theodate’s biggest supporter and a lover of the arts. The family’s collection of French Impressionist paintings can still be found in the Hill-Stead Museum today. The home was built around the paintings of Monet, Cassatt, Degas, and Manet.

Theodate Pope Riddle lived from 1867 to 1946. As an architect, Theodate designed homes and schools throughout Connecticut and New York, including Westover School, Avon Old Farms School, and reconstructing Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace.

Thank you to the Hill-Stead Museum: Executive Director – Dr. Anna Swinbourne, Curator – Melanie Bourbeau, and Chief Advancement Officer – Beth Brett. The book Dearest of Geniuses: A Life of Theodate Pope Riddle by Sandra L Katz was key in making this episode.

Photos of Theodate and paintings from the Hill-Stead collection can be found below, along with a full transcript of the episode. Completely unrelated to the episode, but very cute: here is a live cam of sheep at Hill-Stead.

If you are interested in visiting the Hill-Stead Museum you can get more details on tours at the Hill-Stead Museum website.

The music for our show is by Tim Cahill. Check out his new album, Songs From a Bedroom.

If you like this episode and want to hear other episodes like it check out: Lyndhurst Mansion, Pollock-Krasner House, Sailor’s Snug Harbor, Victoria Woodhull’s Murray Hill Mansion.

Below is a transcript for S3E1 of Someone Lived Here at the Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington, Connecticut. If you have any questions about the show or suggestions on how to make it more accessible please reach out at someonelivedhere@gmail.com.

Kendra Gaylord (00:02):

To start the season, we are at the Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington, Connecticut. The museum was once the home of Theodate Pope Riddle, who was it’s architect and designer. It’s also the home of art you would expect to see at the MET: Paintings from Monet, Degas, Cassatt. Although Theodate lived a life of wealth and privilege, she also experienced immense trauma as a survivor of the Sinking of the Lusitania and was always searching for answers in the metaphysical. Welcome to Someone Lived Here, a podcast about the places people called home. I’m your host Kendra Gaylord.

Kendra Gaylord (00:42):

We’re inside a large white Colonial Revival home, with colossal columns on the front porch and a structured, detailed design. Inside this house, are remarkable Impressionist paintings, but before we look at those, I want to look at a small pen and ink sketch tucked on the second floor. It’s a drawing of a home that helped inspire this house, not because Theodate liked it, but because she didn’t. Theodate was born with the name Effie Pope in 1867. Her parents came from different social standings and religions. Theodate’s mother, Ada, went to private schools, her family members were politicians and Yale graduates. Theodate’s father, Alfred, came from a devout Quaker family and never went to college. But the two met when they were in their early teens. Alfred gave Ada an engagement ring at 16. The families disapproved and Ada was sent to boarding school. When she was a late teen, her mother died in childbirth and two years later her father died. At 22, she married Alfred, moved into his parent’s house, and was soon a mother to Theodate.

Kendra Gaylord (01:47):

Her father used some of his wife’s inheritance and a loan to become the secretary and treasurer of a Cleveland iron company. By the time Theodate was 10 he was its president. They built a home on Euclid Avenue, known as Millionaire’s Row. Which brings us back to this drawing on the second floor of Hill-Stead. It’s a dark Victorian home made of brick, often referred to as a Richardson Romanesque. There are deep arches leading to the porch that make the interior seem untouchable and foreboding. When it was built Theodate did not like the home, but her mother, Ada, loved it and everything it represented. She had now reentered the high society she had grown up within and wanted her daughter to join her in it.

Kendra Gaylord (02:50):

Which brings us to Farmington Connecticut. Theodate was 19 and beginning to consider college. She was interested in Wellesley as a crush of hers, Belle, planned on attending. But when she visited the campus she said it felt like an asylum. As a side note: This is the second time so far I found Theodate hating victorian architecture, but it is not the last. My favorite is, When she was writing about victorian houses going up she called them fluted flimsy highly colored hen houses, which is both a tongue twister and such a good burn. The place where Theodate would go to school was Miss Porter’s School for Girls. After visiting she decided she would go to the high school calling it “one of the prettiest places.” The buildings at Miss Porter’s School (which is still around today) are all very colonial in style. Theodate’s school experience had ups and downs, she was scolded for asking questions and being “fond of an argument”. She also dealt with extended periods of depression. A 23-year-old teacher, Mary Hillard, always seemed to look out for Theodate. Mary was a more progressive teacher, believing women could be more than wives and mothers. There were many reasons being more than a wife and mother appealed to Theodate, who was desperately looking for a calling.

Kendra Gaylord (04:11):

We’re now going to talk with Melanie Bourbeau, the curator at Hill-Stead Museum. We’re standing in the house that she architected and I want to understand how it came to be. After leaving Miss. Porter’s she went on trip to Europe and had a series of conversations with her father.

Melanie Bourbeau (04:30):

And during that tour, she and her father had a number of heart to heart conversations. According to her diary about what she would do with her life: now that school was done, her love life, all the ins and outs of that, and she wanted something substantive. She thought that maybe she would become a writer or an artist. Her father suggested that she could be his bookkeeper or study political economy, or maybe she’d like to study architecture and there’s no backstory to what made him recommend that. But they subsequently had a concurrent conversation about perhaps having a small farm in Cleveland, on the outskirts of the city. Nothing too elaborate, probably nothing too big, but she then proceeds to write in her diary occasionally if they were not off siteseeing or shopping, “spent the afternoon working on my plans for the farmhouse.” And she also wrote “Am very interested in Papa’s suggestion that I study architecture have been interested in it for two weeks. May it last, that much longer.”

Kendra Gaylord (05:42):

That Grand Tour of Europe where Theodate and her father discussed her future was also where the family’s collection of French impressionist paintings truly began.

Melanie Bourbeau (05:54):

So we’re in the drawing room, the one of the largest rooms in the house and the most formal space where the Pope’s would have entertained numerous times. This house was in fact designed because they were a very social couple and the house is huge for two people. The square footage of the residence itself is around 29,000 square feet. So the drawing room is the most densely hung room in terms of artwork. Above the fireplace today is the French Impressionist piece View of Cap d’Antibes by Claude Monet painted in 1888. That really started Mr. Pope on his journey of collecting impressionist artwork. We know from Theodate’s diary that neither she nor her father were immediately a hundred percent taken with impressionist artwork. Theodate wrote that she gave the impressionist a lot of credit for trying something new, but she also thought they’d gone a little too far and that they were shouting in order to be heard. And she didn’t think this new style had any staying power whatsoever, but when her father eventually made this purchase, she said, “I think it’s the finest impression I’ve yet seen. And we would not have appreciated it as much had we not been in the Midi?”

Kendra Gaylord (07:20):

Although their initial reaction to impressionism was slight confusion. They quickly grew to love and appreciate it.

Melanie Bourbeau (07:27):

Alfred Pope’s motivation for buying artwork was deeply personal. He was not buying these works for any sort of financial gain or, you know, contemplating their monetary appreciation and value. He bought them because he loved them. And he would often use the phrase when he was writing, especially to a fellow collector that he wanted to be able to rise to the works that he was buying. And his collection, he had a very fluid approach to his collection. He would buy works of art, keep them for a period of time. Sometimes a matter of months, sometimes a matter of a few years. And I suspect if they no longer provided some deep visceral reaction in him, he would trade them back in for credit toward future purchases or credit toward another immediate acquisition. So the works that remained in the collection today, I think we can safely say are the ones that most impacted him personally, and that he most loved.

Kendra Gaylord (08:40):

This drawing room has remarkable paintings on every wall. Grainstacks, White Frost Effect shows two grainstacks near Monet’s home in Giverny with purples and pinks, while it’s counterpart mirroring it on the opposite wall Grainstacks, in Bright Sunlight with blues greens and yellows. There is also Degas’ Dancer’s in Pink and a Manet’s The Guitar Player side by side on a wall as they were in 1901. I am so used to seeing paintings on solid walls and in empty rooms. But Here Theodate chose the drapes and furniture fabrics because they tied in with the dancer’s pink dresses. There is furniture all around and the space feels lived in. The best way I can describe it is, warm. When the family returned from Europe, Theodate’s 23rd birthday was quickly approaching, she continued to dream of having a farmhouse, but she didn’t want to be outside of Cleveland, but instead to rent and restore a home in Farmington, Connecticut, close to her former school and to Mary Hillard. Her father was against it, a single, young woman living alone in 1890. Her mother, surprisingly, agreed, but it was not about female independence, but instead a young man. Harris Whitemore was a close family friend, and their parents had been hoping to make a match. Theodate had rejected him time and time again. But Harris was currently living a few towns over and her mother thought proximity might change things. It did not.

New Speaker (10:13):

Theodate found herself making a life of her own and restoring a home. She called it the O’Rourkery playing off her landlords name. She began to cook all her own meals and spent a portion of everyday with Mary Hillard. She hosted a group who discussed their current interests every Saturday. It was through her relationship with Mary that she became more interested in Spiritualism and in the library at. Hill-Stead you can see how deep this interest went.

Melanie Bourbeau (10:44):

And one of the most interesting sections of in the library are the books just around the corner, in the second library Theodate’s books on spiritualism. This was a topic that fascinated her and occupied her mind. Um, if not her wallet for many, many years of her life, she was very interested in the popular notion of contacting the beyond, contacting spirits who had passed on to another life. The largest single subject volume of paper in our archive deals with Theodate’s interest in spiritualism, we have all of the transcriptions of the sittings that either she participated in herself or were sent to her so that she could read them and study them and continue to learn from them.

Kendra Gaylord (11:37):

Although much of Theodate’s research and interest was around speaking with the dead, it is also interesting to look at what made Spiritiualism so appealing to women. At the time many religions and society in general believed that the female body was weak and prone to disease, Spiritualists suggested that it was society that was causing them physical and mental pain like unloving marriages, unwanted pregnancies, tight clothes, and a lack of exercise. Theodate, a woman who had undergone electric treatments and rest cures for her depression (A rest cure was an enforced 6-8 weeks of bed rest in isolation with no reading or creative expression allowed), began to follow the spiritualist recommendations. Now living alone in Farmington she was biking everyday, eating well, and she began to feel a lot more stable.

Kendra Gaylord (12:33):

On her father’s recommendation, she began a correspondence with an art history professor at Princeton. He agreed to teach her privately if she came to the area. Over the following years she would study with professors at Princeton in the winter and spring. 75 years later Princeton would begin to accept women. Hill-Stead started to become a reality in 1896, when the family bought the 250 acres behind Theodate’s current home. Theodate was 29 and was beginning on her first job. Alfred hired an architecture firm. The firm sent plans, but Theodate quickly responded with her completed plans for the 28 room farmhouse and laid out plainly in a letter, “In other words, it will be a Pope house instead of a McKim, Mead, and White.” We’ll tell the rest of Theodate’s story after a quick break.

Kendra Gaylord (13:33):

Hey everyone, its Kendra again, I wanted to give you some quick updates on the show and let you know a bit more of what you can expect from season three. We’re changing up the schedule and instead of episodes coming out every other week, they’re now going to be coming out every month or so, still on Mondays. This will hopefully allow for me to record more throughout the year and spend a bit more time creating each individual episode. Also less long breaks between seasons. We’ve also turned off our Patreon. I want to thank everyone who has been supporting us on the platform so far, your monthly donations have made so much possible including covering our monthly hosting fees so far and getting the software that I use that makes editing this so much easier. If you’re going to really miss the Patreon and you want to continue supporting the show, or if you want to give it a shot, we now have a shop at someonelivedhere.com. There you can get Someone Lived Here mugs or shirts that have funny architecture jokes on them. You can also make donations there. If you just want to support the show directly. I did this mostly because I felt really guilty during the longer periods without new episodes. So this solution will hopefully make me feel a little less stressed and gets you guys fun merch. Both of these changes were made to make the show a bit more sustainable for me since this is a one person podcast.

Kendra Gaylord (14:59):

And now for the thing that I just thought would be fun. Someone Lived Here now has a YouTube channel. The videos on there are designed to be a way to talk about houses and history in a more visual medium. Some stuff is about historic homes. Some stuff is about houses in pop culture, like TV shows, movies, video games. If you’re interested in researching your own apartment, I made a video called find the history of your New York City apartment or Monica Geller’s. In it I use the apartment from Friends to show how to use the online tools I use when researching for these podcast episodes. So from it, you might be able to find 1950s images of your apartment along with blueprints and maps of your area going back to the 1880s. Even if you don’t live in New York, there are elements that are the same, no matter where you live. So be sure to subscribe if you’re interested at all and we may have some additional bonus stuff coming revolving around the podcast. I put a link to the shop and to this YouTube channel in the show notes as always. Thank you so much for listening to the show. It means so much to have you here learning about really cool people with me. So let’s get back to the episode and see what Theodate’s up to.

Kendra Gaylord (16:18):

We’re now walking into the dining room, since it tells us a lot about the considerations Theodate was making when creating this home.

Melanie Bourbeau (16:28):

One of the ways that we know Theodate and perhaps her parents were thinking about the placement of artwork in this house, when it was under construction was the dining room fireplace mantle. It’s a very high mantle that was designed proportionally to accommodate this longer narrow pastel drawing jockeys by Degas. So this work of art has hung here from day one. When the family moved into this house in the middle of June 1901, and quite honestly, no other work of art in the collection would even fit there. So this was always viewed as what would be the focal point of this room and the color cues for this work of art, the blues and the greens are reflected in the carpeting, the wallpaper in fact, even some of the china and Asian table coverings that the family acquired.

Kendra Gaylord (17:29):

We’re now going to work our way upstairs to one of the many guest rooms. This one is called the green room,

Melanie Bourbeau (17:36):

Given its name that reflects the carpet color of the wallpaper color. And this is the room that today features the one remaining painting in the collection by Mary Cassatt’s Sara Handing a Toy to the Baby was one of three works of art that Mr. Pope bought after moving into this house.

Kendra Gaylord (17:58):

Mary Cassat was actually a friend of the family and she was hosted here at Hill-Stead. One of the things that made it so comfortable for guests staying here was there was a bathroom attached to every bedroom, which is pretty luxurious for a house that was built in 1901. We’re going into one of these bathrooms and that colonial feel in every part of this house is no different here.

Melanie Bourbeau (18:19):

Great bathtub, you know, short, but very deep and you know, beautiful view out that window.

Kendra Gaylord (18:26):

Now are all the toilets, the style.

Melanie Bourbeau (18:29):

Yeah. You know, you could get really elaborate bathroom fixtures back then. Um, but this was the aesthetic that fit this house. So it’s got this, there’s a very colonial revival-ness about that. Probably this not so comfortable wooden seats. So it has this, I always laugh. It’s got this state park outhouse aesthetic to it, but, but it fit the house. You know, like a really fancy elaborate Victorian porcelain toilet just would have been totally out of place here. And what’s interesting is when they were planning this home, Mr. Pope wrote to Theodate about how much he enjoyed the needle baths at the Ritz hotel,

Kendra Gaylord (19:15):

A needle bath was an early version of the shower, and you can understand why that name did not take off. There are no needle baths or showers here. Theodate stuck with the tried and true bath tub.

Kendra Gaylord (19:28):

Another guest room had a shared bathroom with the room where Theodate stayed. Mary Hillard’s had began working at a new school, slightly further away, but in the summers she often stayed at Hill-Stead. Theodate wrote in her diaries, “We are very apt to sleep together in my rooms and I can slip off to her bed if she goes to sleep.” When Mary was undergoing a surgery, Theodate was offended when her parents who were visiting a sick Uncle did not ask after Mary, “Mary is to me what Uncle Twing is to them and they either do not see it or ignore it. She is of course, more to me than that.”

Kendra Gaylord (20:06):

There were other close relationships over the years as well, Her doctor, a neurologist named Charles. A woman named Laura who she invited to Hill-Stead, 4 words are blacked out from this diary entry, but what remains is “Laura spent the night with me in Mary’s room. I am just so happy today it has changed the whole tenor of my mind.” She had friendships and acquaintances, and despite initially hating the socialite world of her mother, she seemed quite at home in it.

Kendra Gaylord (20:34):

Before we go to Theodate bedroom, what started out as her parent’s room and then became her own. I want us to look at the linen closet that gives us a bit more insight about Theodate’s mother.

Melanie Bourbeau (20:48):

This is the linen and it is floor to ceiling, both sides of the room of drawers and cupboards. And it is still pretty full of, um, blankets and pillows, monogrammed color coordinated bath towels.

Kendra Gaylord (21:09):

What I love about this room is how smart its is laid out. Every closet I have ever put my sheets in, ends up being an absolute mess, with things getting pushed to the back to never been seen until the next time I move. But here, the entire walls is well lit and full of different size compartments for different needs. The room is large enough that you can iron and fold laundry within it. Both the bathrooms and this room show me that Theodate was not just building this house to show off paintings, but making the ins and outs of life more comfortable. I also asked Melanie about those monograms, which appear to be Theodate’s mothers in a very big romantic calligraphy

Melanie Bourbeau (21:47):

So that ABP is Mrs. Pope. And so everything she had was monogrammed, bath towels, bath mats, pillows, pillow cases, sheets, handkerchiefs, tablecloths napkins, placemats

Kendra Gaylord (22:04):

Clearly Theodate’s mother liked monograms. And the ornate letters standing for Ada Brooks Pope are very different than the symbol that Theodate would choose for herself. It’s made up of very straight lines, a backwards L than a vertical line and another L all underlined the symbol was created on a camping trip with Mary and Mary’s younger brother, John, meant to symbolize the group of three together and Theodate and symbol did not just stay in the linen closet. Although it’s there too.

Melanie Bourbeau (22:36):

That is her symbol that she had on stationary. Her automobiles were monogrammed with it, there’s a woven little pouch with it cross stitched in pink on it. As an architect, she had these brass plates with her signature and that symbol that got fixed to various of her buildings. She used it for everything.

Kendra Gaylord (23:05):

There’s even a variation of it on the grave of Mary’s younger brother, John who died of typhoid fever at 26. It was his death that reinforced Theodate’s attention to spiritualism. She would sit down for readings and communications with the dead, analyze scripts, and fund research. Mary went on to found and be the first headmistress of Westover school, a school for girls in Connecticut. Theodate’s father and his friend Harris Whitmore, the young man Theodate had refused to marry, excitedly funded it. Theodate built the campus and one evening the pair drove down to look at the foundations. Mary saw how enormous it all was. Theodate responded, “Let your spirit fill the buildings.”.

Kendra Gaylord (23:51):

Four years after the opening of Westover school Theodate’s father died. With his death she lost her biggest cheerleader. When she didn’t want to marry Harris, he told her she never had to marry. When she changed her name to Theodate, he wrote her new name in the family Bible. When she wanted to be an architect, he commissioned her first building. He really believed in her.

Kendra Gaylord (24:18):

After Alfred’s death began a series of eventful years for Theodate. She adopted a two year old boy Gordon. She was commissioned to build a house on Long Island and another school in Connecticut. And then at age 48, she was traveling to London on the Lusitania. Theodate’s protege in psychical and spiritualist research, Edwin Friend was traveling to London to meet with his English counterparts. She had decided to join him, bringing her maid Emily Robinson. Europe was in the midst of World War One and the German Embassy had placed a warning in the paper. Theodate read that paper after the ship took off from New York City, she suggested if anything happened, they would meet on the deck.

Kendra Gaylord (25:10):

The first five days of the trip went smoothly. On the sixth day, the ship was rerouted to Ireland and Edwin and Theodate were walking on the deck when the Lusitania was hit by a torpedo from a German submarine, there was a loud impact and then a large explosion. The front of the ship was completely underwater. Only 11 miles from the shore. Theodate then saw her maid, Emily Robinson, coming onto the deck. The three found life jackets and Edwin tied them on both of the women. They then needed to jump Theo asked Edwin to go first. He stepped over the ropes and the railing and jumped. He popped back up from the waters signaling for them to join him. Theodate slipped, lost her footing and then kind of jumped in the water. She remembers not being able to reach the surface swallowing water and heard her voice say, “This is of course the end of life for me.” When she reached the surface she was surrounded by broken furniture, debris, and bodies. She was then struck hard in the head and was knocked unconscious. She drifted in and out for hours. A patrol boat pulled her body out and could not feel a pulse. She was placed on the deck with the dead. Another survivor, went around to the bodies and thought she saw Theodate’s eyelids flicker. Two crewmen revived her.

Kendra Gaylord (26:38):

Edwin Friend and Emily Robinsons bodies were never found. The Luisitania had sank in 18 minutes and 1,197 people died. Theo recovered in the home of a Quaker family in Cork. She would spend the summer in Europe, not yet ready to make the trip back. While she recovered she received loving letters from a friend John Riddle.

Kendra Gaylord (27:13):

We’re now going to head back to Hill-Stead and look at one more room before we take the hidden passage to Theodates.

Melanie Bourbeau (27:20):

And this room is set up today to reflect it’s used by Theodate’s husband after she and her husband, John Riddle, eventually moved into this house. They were married in the spring of 1916, exactly 364 days after she survived the sinking of the Lusitania. Theodate and John had known each other for about a decade before they married. Theodate was 49. John was 51. It was a first marriage for both of them. And it was really quite a shock to everybody that Theodate knew that she was finally going to get married. And in fact, one of the first people that she wrote to, to share the news was the family’s Butler, Earnest Bohlen, instructing him that, you know, on this particular date, please announce my engagement to the rest of the household staff. And so he promptly wrote her a reply and it was very short and succinct and it was “My dear Ms. Pope shocked I was at first, but after a thought, why not?” So we can go right, right through here.

Kendra Gaylord (28:23):

So this is, this is our secret tunnel? In true Theodate fashion. She reconfigured the closet to connect their room.

Melanie Bourbeau (28:33):

So the master bedroom is the, you know, befitting the master bedroom, the largest bedroom in the house.

Kendra Gaylord (28:40):

The decor in this bedroom is very different than what we’ve seen in every other room, especially when it comes to the art.

Melanie Bourbeau (28:46):

The artwork is definitely different in these rooms, it’s got this very familial, maternal feel to it and the needle work, there are two embroidered needle works and an embroidery and a cross stitch are just indicative of Theodate. It’s love of old things and given how her own house had been furnished in this very old time colonialeque manner, the needle works just make total sense for Theodate’s own personal interests.

Kendra Gaylord (29:20):

This needlework, is a great way to understand what was going on with the Colonial Revival. Beverly Gordon, a textile interpreter and professor emeritus in Design Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote about this in her paper about the paradox of colonial revival needlework. “In its earliest phases, the Colonial Revival was largely a reactionary response on the part of a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant elite that was losing its sense of dominance and control. The rising tide of immigration was changing… the country, and many who were alarmed by depressions, labor unrest, and the apparent end of the frontier sought to set themselves apart by tracing their lineage to ancestors of “solid” pioneer stock.” A lot of Beverly Gordon’s piece is discussing the colonial style in needlework that made a comeback in this era (1875-1940), symmetrical designs, flower baskets, swags, teacups, wreaths. And needlework which was initially seen as something for rural, disadvantaged women, had become a popular trend.

Kendra Gaylord (30:33):

The Colonial Revival can be seen as romanticism of a non-industrial, more rural version of the United States and a reaction to Victorian excess. But it was raising up the art and the architecture and pushing down the more honest historical past, while distancing itself from the current reality. When I look at this house, I see that Theodate had true appreciation for the Colonial style, both in architecture and in art. Her library is a testament to how much she studied it’s form and tried to understand it’s context.

Kendra Gaylord (31:10):

We’re going to head outside and I want to to talk about Theodate’s final and largest project: The Avon Old Farms School. She built this school for boys in memory of her father. The school feels like an English village, like it could’ve been Harry Potter’s safety school if he didn’t get into Hogwarts. Upon it’s completion, it got her the type of praise that would have made her father so proud. She received accolades from the architecture community that she had long been shut out of. The school was featured in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects and she was invited to be a fellow. She received letters from colleagues praising her work, even if they were often addressing her as Mr. or Sir.

Kendra Gaylord (31:50):

We’re now heading to the Sunken Garden. It was a one acre garden. It had been let go while Theodate was still in the home, but it has been revived in a different form.

Melanie Bourbeau (32:05):

So we’re going down like nine, 10 steps into a one acre sunken perennial garden.

Kendra Gaylord (32:11):

When a team was starting on reconstruction of this garden in the 1980s they found a plan by Beatrix Farrand. She was a prolific landscape architect in the early 1900s, and was commissioned to design over a hundred gardens. But only a handful of her designs still exist. Although this Hill-Stead plan had never been put in place, they decided to create the garden how she outlined it.

Melanie Bourbeau (32:34):

Beatrix Farrand’s approach. You can tell that the taller plantings to the back, and she was very much in favor of what she referred to these kind of round tall, rounded evergreens as bullets. And she favored masses of color. And that kind of, you know, as the taller plants would sway in the breeze that the movement that would be a part of the garden. This is just a, it’s a wonderful example. And it’s, it’s one of the few places to my knowledge that is completely publicly accessible year round.

Kendra Gaylord (33:11):

When Theodate died, her will requested that she be buried at Hill-Stead, but the town of Farmington would not permit a private cemetery, this would be one of the very few things her will would not be able to accomplish. Now were going to talk to Dr. Anna Swinbourne, the Executive Director of Hill-Stead Museum on how Theodate’s legacy and her will lives on.

Melanie Bourbeau (33:35):

I’m actually after my interview with you meeting with a probate judge who is so fascinated by Theodate’s last will and testament that she’s taught classes on it. She thinks it’s like the Mona Lisa of wills.

Kendra Gaylord (33:49):

Could we expect anything less from Theodate? She also outlined her home continuing on as a museum, keeping on the entire staff.

Anna Swinbourne (33:57):

What seems typical to her character, incredibly fastidious, exactly what she wanted about everything. She did leave an amount of money as an endowment. The dividends on that money though, only pay about 10% of our operating budget. So I like to tell people she could have imagined the internet before she would have been able to predict the appreciation of the assets, particularly the paintings. One of the parts of her will that most people interpret as the most limiting is that nothing can leave the collection and nothing can be added to the collection so that it is static. I have studied art and artists long enough to understand sometimes your best work happens when facing a limitation with that unmovable in our landscape, it really forces us to just be more creative. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I think it’s part of what makes us really really special.

Kendra Gaylord (34:56):

Hill-Stead Museum is currently in the final stages of completing a project within the carriage barn.

Melanie Bourbeau (35:03):

Really what we’re doing. We don’t touch the footprint at all, but we are lining it with a skin and interior skin so we can put all of the good juicy climate control, thermal envelope, ADA compliant features into what’s already there. So the objective has been to create a space within the historic space, but that will give us options that we’ve never had from a programming standpoint.

Kendra Gaylord (35:35):

120 years after Theodate finished this home, it continues to be used in so many ways. Concerts on the front porch, historic house tours, a farm with sheep and bees, a poetry festival in the garden. And before we go, I want to look at one more thing in that garden, a large sundial that Theodate had studied and created to bring together this space. On its side it reads the Latin, “Ars longa, vita brevis” in this home where artwork is surrounded by books and pillows and desks and nature. There’s always the reminder “Art is long, life is brief.”

Kendra Gaylord (36:22):

Thank you to Dr. Anna Swinbourne, Melanie Bourbeau, Beth Brett, and everyone at Hill-Stead Museum. The book Dearest of Geniuses, A Life of Theodate Pope Riddle by Sandra L Katz was key in putting together this episode. And thank you for listening to the first episode of season 3. I’d love to hear what you think of the show, so leave a review on Apple Podcasts or comment on the episode blog post if you want to discuss it further. There have been a lot of changes to the website including a new shop, so be sure to check it out.Final thank you to Tim Cahill for our music. He just released a new album called Songs From a Bedroom, which is really great. I am your host Kendra Gaylord, This was Someone Lived Here.

Sources:

Dearest of Geniuses: A Life of Theodate Pope Riddle by Sandra L Katz.

Western Reserve Historical Society. Photo of Alfred Pope’s 3648 Euclid Ave Home in 1920

Miss Porters School in Historic Buildings of Connecticut

Hill-Stead Museums Collections: Impressionist Paintings, Linens, Pope Riddle Family, Sunken Garden

The Luisitania Resource: History, Passenger & Crew Biographies and Luisitania Facts

Improving the Past: the Colonial Revival on Long Island from The Long Island Museum of American Art, History and Carriages

Charmingly Quaint and Still Modern: The Paradox of Colonial Revival Needlework in America 1875-1940 by Beverly Gordon

Biography of Beatrix Farrand from The Beatrix Farrand Society

Photo of Hill-Stead sundial by De Justice